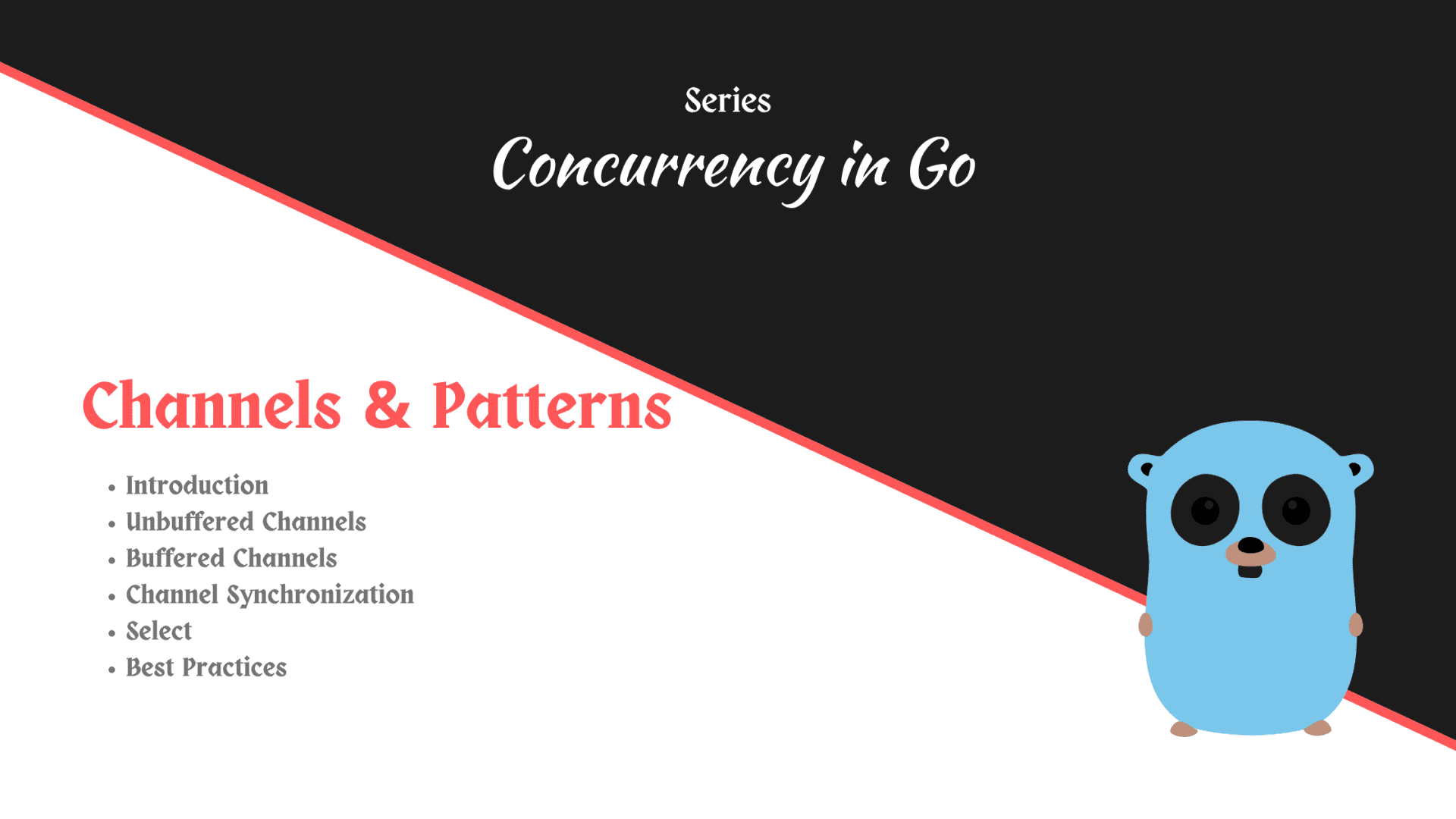

Working with Channels and Patterns

- With Code Example

- September 17, 2023

Series - Concurrency In Go

- 1: The Power of Concurrency in Go

- 2: Understanding Goroutines in Go Language

- 3: Working with Channels and Patterns

- 4: Managing Shared Resources with Mutex

- 5: Synchronization Primitives in the sync Package

- 6: Challenges of Error Handling in Concurrent Code

- 7: Patterns for Effective Concurrency in Go

- 8: Performance Considerations and Optimization in Go

Concurrent programming is a powerful approach for creating performance-tuned and reactive software. Golang , also known as Go, comes in handy with channels to facilitate concurrent communications reliably and beautifully. This article will unveil the concept of channels, explain their part in concurrent programming and provide insights on how to send or receive data through both unbuffered and buffered channels.

Table of Contents

Introduction to Channels

Channels in Go are a fundamental feature that enables safe and synchronized communication between Goroutines (concurrent threads of execution). They act as conduits through which data can be passed between Goroutines, facilitating coordination and synchronization in concurrent programs.

Channels are unidirectional, meaning they can be used either for sending data (<- chan) or receiving data (chan <-). This unidirectional nature helps enforce a clear and controlled flow of data between Goroutines.

Sending and Receiving Data

1. Unbuffered Channels

Unbuffered channels are a type of channel where data is sent and received simultaneously. When a value is sent on an unbuffered channel, the sender will block until there is a corresponding receiver ready to receive the data. Likewise, the receiver will block until there is data available to be received.

Here’s an example illustrating the use of an unbuffered channel:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

ch := make(chan int) // Create an unbuffered channel

go func() {

ch <- 42 // Send data into the channel

}()

time.Sleep(time.Second) // Give the Goroutine time to execute

value := <-ch // Receive data from the channel

fmt.Println("Received:", value)

}

In this example, a Goroutine sends the value 42 into the unbuffered channel ch, and the main Goroutine receives it. The program will block until both the sender and receiver are ready.

2. Buffered Channels

Buffered channels allow you to send and receive data asynchronously with a specified buffer size. This means that you can send multiple values into the channel without waiting for a receiver, as long as the buffer is not full. Similarly, the receiver can read from the channel without waiting for a sender, as long as the buffer is not empty.

Here’s an example illustrating the use of a buffered channel:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

ch := make(chan string, 2) // Create a buffered channel with a capacity of 2

ch <- "Hello" // Send data into the channel

ch <- "World"

fmt.Println(<-ch) // Receive data from the channel

fmt.Println(<-ch)

}

In this example, we create a buffered channel ch with a capacity of 2. We can send two values into the channel without blocking, and then we receive and print those values. Buffered channels are useful when you want to decouple the sender and receiver, allowing them to work independently within the buffer size constraints.

Channel Synchronization

Channel synchronization in Go is a technique used to coordinate and synchronize the execution of Goroutines (concurrent threads) through the use of channels. Channels facilitate safe and ordered communication between Goroutines, allowing them to signal each other when specific tasks are completed or data is ready. This synchronization mechanism is vital for ensuring that Goroutines execute in a controlled and synchronized manner.

Here are some common scenarios where channel synchronization is useful:

Waiting for Goroutines to Finish: You can use channels to wait for one or more Goroutines to complete their tasks before proceeding with the main program.

Coordinating Parallel Tasks: Channels can be used to orchestrate multiple Goroutines performing tasks concurrently, ensuring that they complete their work in a specific order or synchronize at specific points.

Collecting Results: Channels can be used to collect and aggregate results from multiple Goroutines and then process them once all Goroutines have finished their work.

Let’s explore these scenarios with examples:

1. Waiting for Goroutines to Finish

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func worker(id int, wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

defer wg.Done()

fmt.Printf("Worker %d is working\n", id)

}

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for i := 1; i <= 3; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go worker(i, &wg)

}

wg.Wait() // Wait for all workers to finish

fmt.Println("All workers have finished.")

}

In this example, we have three worker Goroutines. We use a sync.WaitGroup to wait for all of them to finish their work before printing “All workers have finished.”

2. Coordinating Parallel Tasks

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

ch := make(chan int)

for i := 1; i <= 3; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func(id int) {

defer wg.Done()

fmt.Printf("Goroutine %d is working\n", id)

ch <- id // Send a signal to the channel when done

}(i)

}

// Wait for all Goroutines to signal completion

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(ch) // Close the channel when all Goroutines are done

}()

for id := range ch {

fmt.Printf("Received signal from Goroutine %d\n", id)

}

fmt.Println("All Goroutines have finished.")

}

In this example, we have three Goroutines that perform work and signal their completion using a channel. We use a sync.WaitGroup to wait for all Goroutines to finish, and a separate Goroutine listens to the channel to know when each Goroutine has completed its work.

3. Collecting Results

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func worker(id int, resultChan chan<- int, wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

defer wg.Done()

result := id * 2

resultChan <- result // Send the result to the channel

}

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

resultChan := make(chan int, 3)

for i := 1; i <= 3; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go worker(i, resultChan, &wg)

}

wg.Wait() // Wait for all workers to finish

close(resultChan) // Close the channel when all results are sent

for result := range resultChan {

fmt.Printf("Received result: %d\n", result)

}

}

In this example, three worker Goroutines calculate results and send them to a channel. The main Goroutine waits for all workers to finish, closes the channel, and then reads and processes the results from the channel.

These examples illustrate how channel synchronization can be used to coordinate and synchronize Goroutines in various concurrent programming scenarios in Go. Channels provide a powerful mechanism for safe and orderly communication between Goroutines, making it easier to write concurrent programs that behave predictably and reliably.

Select Statement: Multiplexing Channels

One of the key tools for managing concurrent tasks is the select statement. In this article, we will explore the select statement’s role in multiplexing channels, a technique that enables Go programmers to synchronize and coordinate Goroutines effectively.

Multiplexing Channels with select

When you have multiple Goroutines communicating through various channels, you may need to coordinate their activities efficiently. The select statement allows you to achieve this by choosing the first channel operation that can proceed.

Here’s a simple example demonstrating the use of select for multiplexing channels:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

ch1 := make(chan string)

ch2 := make(chan string)

go func() {

time.Sleep(time.Second)

ch1 <- "Message from Channel 1"

}()

go func() {

time.Sleep(time.Millisecond * 500)

ch2 <- "Message from Channel 2"

}()

select {

case msg1 := <-ch1:

fmt.Println(msg1)

case msg2 := <-ch2:

fmt.Println(msg2)

}

fmt.Println("Main function exits")

}

In this example, we have two Goroutines sending messages on two different channels, ch1 and ch2. The select statement chooses the first channel operation that becomes available, allowing us to receive and print the message from either ch1 or ch2. The program then continues with the main function, demonstrating the power of channel multiplexing using select.

Using select with a Default Case

The select statement also supports a default case, which is useful when you want to handle situations where none of the channel operations are ready. Here’s an example:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

ch := make(chan string)

go func() {

time.Sleep(time.Second * 2)

ch <- "Message from Channel"

}()

select {

case msg := <-ch:

fmt.Println(msg)

default:

fmt.Println("No message received")

}

fmt.Println("Main function exits")

}

In this case, we have a Goroutine sending a message on the channel ch. However, the select statement includes a default case that handles the situation when no message arrives within the expected time. This allows for graceful handling of scenarios where none of the channel operations are ready.

Best Practices and Patterns in Go: Fan-out, Fan-in, and Closing Channels

When it comes to writing clean and efficient Go code, there are certain best practices and patterns that can significantly enhance the quality and performance of your concurrent programs. In this article, we will explore two essential practices: Fan-out, Fan-in and Closing Channels. These patterns are powerful tools for managing concurrency and communication in Go applications.

1. Fan-out, Fan-in

The Fan-out, Fan-in pattern is a concurrency design pattern that allows you to distribute work across multiple Goroutines and then collect and consolidate the results. This pattern is particularly useful when dealing with tasks that can be processed concurrently and then aggregated.

Example of Fan-out, Fan-in

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math/rand"

"sync"

"time"

)

func worker(id int, input <-chan int, output chan<- int) {

for number := range input {

// Simulate some work

time.Sleep(time.Millisecond * time.Duration(rand.Intn(100)))

output <- number * 2

}

}

func main() {

rand.Seed(time.Now().UnixNano())

input := make(chan int)

output := make(chan int)

const numWorkers = 3

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// Fan-out: Launch multiple workers

for i := 0; i < numWorkers; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func(id int) {

defer wg.Done()

worker(id, input, output)

}(i)

}

// Fan-in: Collect results

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(output)

}()

// Send data to workers

go func() {

for i := 1; i <= 10; i++ {

input <- i

}

close(input)

}()

// Receive and process results

for result := range output {

fmt.Println("Result:", result)

}

}

In this example, we create three worker Goroutines that perform some simulated work and then send the results to an output channel. The main Goroutine generates input data, and a separate Goroutine collects and processes the results using the Fan-in pattern.

2. Closing Channels

Closing channels is an essential practice for signaling the completion of data transmission and preventing Goroutines from blocking indefinitely. It’s crucial to close channels when you no longer plan to send data through them to avoid deadlocks.

Example of Closing Channels

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

dataChannel := make(chan int, 3)

go func() {

defer close(dataChannel) // Close the channel when done

for i := 1; i <= 3; i++ {

dataChannel <- i

}

}()

// Receive data from the channel

for num := range dataChannel {

fmt.Println("Received:", num)

}

}

In this example, we create a buffered channel dataChannel with a capacity of 3. After sending three values into the channel, we close it using the close function. Closing the channel signals to any receivers that no more data will be sent. This allows the receiving Goroutine to exit gracefully when all data has been processed.